Govt plans to run registry of sex offenders

Context:

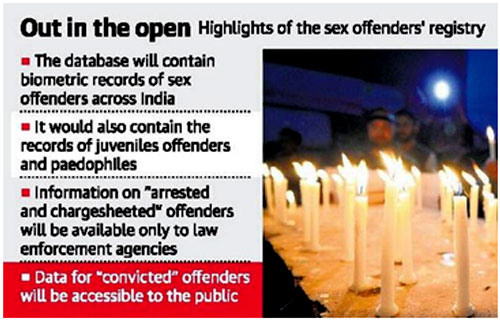

India recently launched a National Database on Sexual Offenders (NDSO), the ninth country to do so. A look at the objectives of and criticism against the idea, and how other countries run their registries:

Broad objective

The Criminal Law Act, 2018, provides for a national registry of sexual offenders. Accessible only to law enforcement agencies, the database will include offenders convicted of rape, gang-rape, under the POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) Act, and of “eve teasing”. It will be maintained by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). At present the database contains 4.4 lakh entries. State police forces have been asked to regularly update the database from 2005 onwards; this will help keep track of released convicts who have moved from one place to another.

There are two reasons for starting the database from 2005. At most prisons, records before 2005 have not been digitised. Second, in many cases, the maximum punishment is life imprisonment which is calculated as 14 years, so many convicted prior to 2005 will have served their sentences. (In 2012, the Supreme Court clarified that life imprisonment would mean an entire lifetime.)

Data to be stored

The database will include names and aliases, identifiers including PAN and Aadhaar, information of date of birth, criminal history, fingerprints and palm prints, and various other details. It will only have details of persons who are aged 18 or more. Whenever the details of a convict are entered into a prison database anywhere in the country, the name will be uploaded to the registry. Appeals against a conviction will have to be updated by state prisons; an accused can be tracked until an acquittal on appeal.

Other countries

Similar databases of sexual offenders are maintained in the US, the UK, Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa and Trinidad & Tobago. While the registry in the US is available to the public and communities, except data on juveniles, other countries limit access only to law-enforcement agencies. Everywhere, only convicted persons are entered.

The US law owes its genesis to a case involving Jesse Timmendequas, a convicted sex offender who, on being released after serving the maximum sentence, raped and murdered a 7-year-old. Community members successfully lobbied for the enactment of a law requiring registration and public notification that a sex offender is living in the community, in the belief that this would allow citizens to take protective measures. Since then, all US states have passed similar legislation, collectively referred to as “Megan’s Law”.

Criticism

In some western countries, there have been demands for a review of the decision to maintain a registry amid a view that it does not serve as a deterrent or help people who have survived sexual violence. In India, critics have pointed out most sex crimes are committed by a person known to the victim; NCRB data of 2015 states that out of 34,651 reported rape cases, 33,098 were committed by people known to the victim. “Once such a registry comes into being, I am concerned that it might lead to people not reporting rapes or sexual offences, because most of them are by people known to the victims,” PTI quoted Bharti Ali of HAQ Centre for Child Rights as saying.