Growth and the Farmer

Context:

- Recently, Montek Singh Ahluwalia’s book, Backstage: The Story behind India’s High Growth Years, was released. It is an account of India’s economic reform journey for about 30 years.

Policy Debates and Choices in the Agri-Food Space:

- From 2004-05 to 2013-14, it was believed that inclusive growth is not feasible unless agriculture grows at about 4 per cent per year while the overall economy grows at about 8 per cent annually.

- The reason was simple: More than half of the working force at that time was engaged in agriculture and much of their income was derived from agriculture.

- The main instrument of agricultural strategy was the Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY), which gave more leverage to states to allocate resources within agriculture-related schemes.

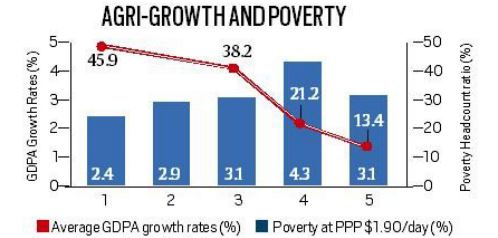

- This, along with other infrastructure investments in rural areas, had a beneficial impact on agri-growth, which increased from 2.9 per cent in 1999-04 to 4.3 per cent during (2009-10 to 2013-14).

Agricultural Growth and Poverty Reduction:

- Agri-GDP growth had a significant impact on poverty reduction. The rate of decline in poverty (head count ratio), about 0.8 per cent per year during 1993-94 to 2004-05, accelerated to 2.1 per cent per year.

- Instead of celebrating this success of the growth strategy in alleviation of poverty, many advocated food subsidy under the Right to Food Campaign.

- Government and national advisory council came up with a proposal to subsidise 90 per cent of people by giving them rice and wheat at Rs 3/kg and Rs 2/kg. This led to India end up importing grains to the tune of 13-15 million tonnes per year.

- Montek favoured a cap at 40 per cent of the population to be covered under the Food Security Act as the poverty ratio (HCR) in 2011-12 was 22 per cent

- He also favoured providing smart cards to the beneficiaries so that they could opt for buying more nutritious food rather than just relying on rice and wheat.

- That would have also allowed diversification of agriculture and augmented farmers’ incomes

Consumer Bias:

- Montek also argued against export bans on agricultural commodities as these impacted farmers’ incomes adversely. But the government taking the consumer’s side, as that was considered pro-poor.

- This reduced the incentives for farmers, who then had to be compensated by increasing input subsidies. Today, the food subsidy is the biggest item in the Union budget’s agri-food space. In the current budget, it is provisioned at Rs 1,15,570 crore.

- The government has been also asking the Food Corporation of India (FCI) to borrow from myriad sources, and not fully funding the food subsidy, which should logically be a budgetary item. This would led to the effective amount of food subsidy comes to Rs 3,57,688 crore. This displays the consumer bias in the system.

Conclusion:

- The Economic Survey of 2019-20 makes a case for restricting food subsidy to 20 per cent of the population — the head count poverty in 2015 as per the World Bank’s $1.9/per capita per day (PPP) definition was only 13.4 per cent.

- For the others, the issue prices of rice and wheat need to be linked to at least 50 per cent of the procurement price or, even better, 50 per cent of the FCI’s economic cost.

- Unless we make progress on this front, it is difficult to unlock resources for the growth of agriculture which slumped from 4.3 per cent in 2009-14 to 3.1 per cent in 2014-19.

Source: The Indian Express