Is heat in India set to get worse?

10, Mar 2023

Prelims level : Environment

Mains level : GS-III Environment & Biodiversity | Disaster and disaster management

Why in News?

- In India, the month of February in 2023 has been regarded as the hottest so far since 1901.

Highlights:

- A study published in July 2021 in The Lancet, which took into account the data from two decades (2000-2019), notes that about 50 lakh people die every year (on average) across the world due to extreme temperatures.

- Further, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) highlights the fact that extreme heat events would continue to grow with the rise in global warming and that every increment of warming matters.

Increased temperatures in India:

- According to a study on the historical climate in India by the Centre for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP), the temperature in the country has been increasing steadily both during summer as well as winter months.

- The study further recorded an increase in maximum and minimum temperatures over 30 years (1990-2019) at 0.9°C and 0.5°C, respectively.

- In India, the temperatures during summer months have increased by 0.5°C to 0.9°C in several districts in States such as the Northeastern States, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat.

- Similarly, the temperatures in winter months have also increased by 0.5°C to 0.9°C in about 54% of districts in the country.

- The Northeastern States have experienced higher levels of warming as compared to the southern States.

- This significant increase in temperatures has led to suffering and death in extreme cases and it further adversely impacts agriculture and other climate-sensitive sectors which play a key role in ensuring the livelihoods and well-being of people.

- A joint report by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, and the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre says that an extreme-heat event which would happen only once in every 50 years without the influence of humans on climate is now likely to happen five times on account of human-induced climate change.

- Further, the report states that such extreme-heat events would occur 14 times if the warming is under 2°C and occur 40 times if the warming is kept under 4°C.

Climate projections:

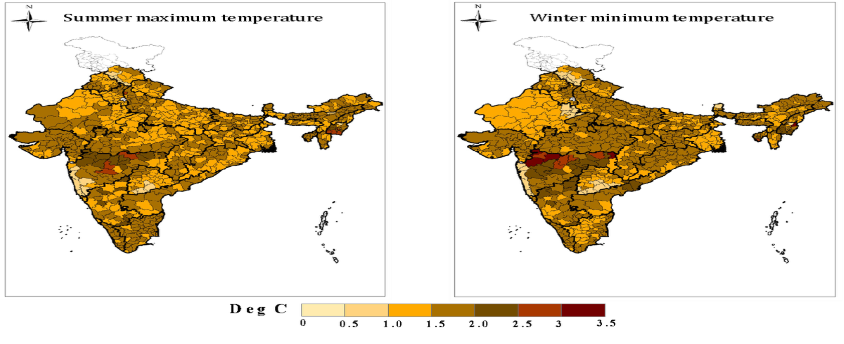

- As per the climate projections by the CSTEP study for a 30-year period between 2021-2050, the maximum temperature during the summer months would increase even under a “moderate emissions” scenario.

- The increase would be much higher in case of “higher emissions” scenarios and would likely be more than 2°C and up to 3.5°C in about 100 districts of the country and 1.5°C to 2°C in around 455 districts.

- Further, the minimum temperatures in winter months are expected to increase by 0.5°C to 3.5°C in the future.

- The highest warming of 2.5°C to 3°C is estimated in less than 1% of the districts, and an increase of 1°C to 1.5°C is estimated in over 485 districts of the country.

- Further, there has been a change in the diurnal temperature range (DTR), which is the variation between high temperature and low temperature in a single day.

- A recent study supported by the Department of Science and Technology has highlighted an alarming rate of decline in DTR between 1991 and 2016, especially in the northwest parts of the Gangetic plain, and central India agro-climatic zones.

Implications of heat stress:

- The increase in summer maximum and winter minimum temperatures in the coming years can negatively impact the growth of plants, ecology, and the carbon economy as extreme variations in temperature affect the quality of the soil.

- The decline in the DTR indicates an asymmetrical increase in the minimum temperature compared to the maximum, which ultimately could increase the risk of heat stress which could result in droughts, instances of crop failures, and higher morbidity and mortality rates.

- A joint report by IFRC and others also predicts that heat waves would surpass human threshold levels to withstand them physiologically as well as socially.

- This could result in large-scale suffering, death, and migration.

- In the context of urban areas, the combined effects of warming coupled with the rapid rate of urbanisation would increase the number of people at risk of extreme heat.

- As per an International Labour Organization (ILO) report, India would lose about 5.8% of working hours in 2030 on account of heat stress and the loss in escorts such as agriculture and construction would be close to 9.04%, which translates to 3.4 crore full-time jobs.

Way forward:

- It has become important for the States to involve and share responsibility with other stakeholders to fully implement the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and improve early warning systems, public awareness, and come up with heat action plans.

- District-level heat hotspot maps must be prepared which can help various departments of the State in formulating long-term actions to reduce the impact of extreme heat.

- The policymakers and the stakeholders must also look at innovative strategies to address the challenges of extreme heat. Some of the innovative strategies adopted across the world include:

- Setting up emergency cooling centres similar to those in Toronto and Paris.

- Public awareness through survival guides that are strategically displayed in Athens.

- Installing –

- White roofs like in Los Angeles

- Green rooftops similar to those in Rotterdam

- Self-shading tower blocks like in Abu Dhabi

- Green corridors in Medellin