Category: Citizenship

Over 16 lakh people renounced Indian citizenship since 2011

10, Feb 2023

Why in News?

- According to data provided by the government in Rajya Sabha, more than 16 lakh Indians renounced their Indian citizenship since 2011 including 2,25,620 last year.

What is Citizenship?

Constitutional Provisions:

- Citizenship is listed in the Union List under the Constitution and thus is under the exclusive jurisdiction of Parliament.

- The Constitution does not define the term ‘citizen’ but details of various categories of persons who are entitled to citizenship are given in Part 2 (Articles 5 to 11).

Acquisition of Indian Citizenship:

- The Citizenship Act of 1955 prescribes five ways of acquiring citizenship, viz, birth, descent, registration, naturalisation and incorporation of territory.

Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019:

- The Act amended the law to fast-track citizenship for religious minorities, specifically Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians, from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan who entered India prior to 2015.

- The requirement for them to stay in India for at least 11 years before applying for Indian citizenship has been reduced to five years.

Why do People Relinquish Citizenship?

- For India with newer generations holding passports of other countries, some older Indians are choosing to leave to be with family settled overseas.

- In some high-profile cases, people who leave India may be fleeing the law or fear legal action for alleged crimes.

- The post-Independence diasporic community has been going (out of India) for jobs and higher education but the pre-Independence diasporic movement was completely different, witnessing forced and contractual labour.

- Since India does not provide dual citizenship, therefore one has to renounce his/her Indian Citizenship for acquiring citizenship of another country.

- Countries where Indians have been migrating for long or where people have family or friends would be more automatic choices, as would considerations such as easier paperwork and more welcoming social and ethnic environments.

What are the Ways to Renounce Citizenship in India?

Voluntary Renunciation:

- If an Indian citizen wishes, who is of full age and capacity, he can relinquish citizenship of India by his will. When a person relinquishes his citizenship, every minor child of that person also loses Indian citizenship.

- However, when such a child attains the age of 18, he may resume Indian citizenship.

By Termination:

- The Constitution of India provides single citizenship. It means an Indian person can only be a citizen of one country at a time. If a person takes the citizenship of another country, then his Indian citizenship ends automatically.

- However, this provision does not apply when India is busy in war.

Deprivation by Government:

- The Government of India may terminate the citizenship of an Indian citizen if;

- The citizen has disrespected the Constitution.

- Has obtained citizenship by fraud.

- The citizen has unlawfully traded or communicated with the enemy during a war.

- Within 5 years of registration or naturalisation, a citizen has been sentenced to 2 years of imprisonment in any country.

- The citizen has been living outside India for 7 years continuously.

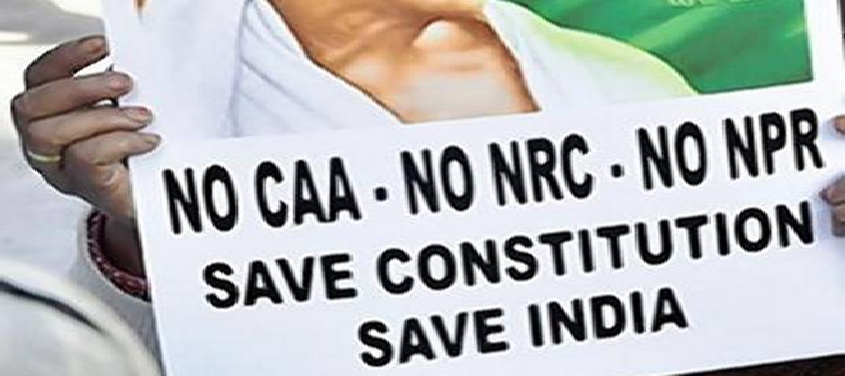

NESO holds ‘Black Day’ to Mark Three Years of CAA

12, Dec 2022

Why in News?

- The North East Students’ Organisation (NESO) observed the third anniversary of the passage of the contentious Citizenship (Amendment) Bill (CAB), which subsequently became the Citizenship (Amendment) Act or CAA” as a black day.

About the CAA and Foreigners Tribunal:

- The Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019 that seeks to give citizenship to refugees from the Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, Sikh and Zoroastrian communities fleeing religious persecution from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, who came to India before 31st December, 2014.

- Residential requirement for citizenship through naturalization from the above said countries is at least 5 years. Residential requirement for citizenship through naturalization for others is 11 years.

- The Act applies to all States and Union Territories of the country.

- The beneficiaries of Citizenship Amendment Act can reside in any state of the country.

- In 1964, the govt. brought in the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order.

- Advocates not below the age of 35 years of age with at least 7 years of practice (or) Retired Judicial Officers from the Assam Judicial Service (or) Retired IAS of ACS Officers (not below the rank of Secretary/Addl. Secretary) having experience in quasi-judicial works.

- The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has amended the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964, and has empowered district magistrates in all States and Union Territories to set up tribunals (quasi-judicial bodies) to decide whether a person staying illegally in India is a foreigner or not.

- Earlier, the powers to constitute tribunals were vested only with the Centre.

- Typically, the tribunals there have seen two kinds of cases: those concerning persons against whom a reference has been made by the border police and those whose names in the electoral roll has a “D”, or “doubtful”, marked against them.

Who are illegal immigrants?

- According to the Citizenship Act, 1955, an illegal immigrant is one who enters India without a valid passport or with forged documents, or a person who stays beyond the visa permit.

What is NRC?

- The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is meant to identify a bona fide citizen.

- In other words, by the order of the Supreme Court of India, NRC is being currently updated in Assam to detect Bangladeshi nationals who might have entered the State illegally after the midnight of March 24, 1971.

- The date was decided in the 1985 Assam Accord, which was signed between the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the AASU.

- The NRC was first published after the 1951 Census in the independent India when parts of Assam went to the East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

- The first draft of the updated list was concluded by December 31, 2017.

Arguments against the Act:

- The fundamental criticism of the Act has been that it specifically targets Muslims. Critics argue that it is violative of Article 14 of the Constitution (which guarantees the right to equality) and the principle of secularism.

- India has several other refugees that include Tamils from Sri Lanka and Hindu Rohingya from Myanmar. They are not covered under the Act.

- Despite exemption granted to some regions in the North-eastern states, the prospect of citizenship for massive numbers of illegal Bangladeshi migrants has triggered deep anxieties in the states.

- It will be difficult for the government to differentiate between illegal migrants and those persecuted.

Arguments in Favour:

- The government has clarified that Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh are Islamic republics where Muslims are in majority hence they cannot be treated as persecuted minorities. It has assured that the government will examine the application from any other community on a case to case basis.

- This Act is a big boon to all those people who have been the victims of Partition and the subsequent conversion of the three countries into theocratic Islamic republics.

- Citing partition between India and Pakistan on religious lines in 1947, the government has argued that millions of citizens of undivided India belonging to various faiths were staying in Pakistan and Bangladesh from 1947.

- The constitutions of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh provide for a specific state religion. As a result, many persons belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian communities have faced persecution on grounds of religion in those countries.

- Many such persons have fled to India to seek shelter and continued to stay in India even if their travel documents have expired or they have incomplete or no documents.

- After Independence, not once but twice, India conceded that the minorities in its neighbourhood is its responsibility. First, immediately after Partition and again during the Indira-Mujib Pact in 1972 when India had agreed to absorb over 1.2 million refugees. It is a historical fact that on both occasions, it was only the Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and Christians who had come over to Indian side.

Home Ministry seeks More Time to frame CAA Rules

08, Feb 2022

Why in News?

- The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) sought has asked the parliamentary committee for more time to frame the rules of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA), on the Grounds that Consultation process is on.

About the News:

- The MHA had sought another extension on January 9 from the parliamentary committees on subordinate legislation in the Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha to frame the rules of the CAA.

- Besides the consultation process, MHA said that the construction of the rules had been delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Without the rules being framed, the Act cannot be implemented.

- A senior government official said that MHA stated two grounds for seeking a three-months’ extension to notify the rules — consultation process and COVID-19.

About the CAA and Foreigners Tribunal:

- The Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019 that seeks to give citizenship to refugees from the Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, Sikh and Zoroastrian communities fleeing religious persecution from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, who came to India before 31st December, 2014.

- Residential requirement for citizenship through naturalization from the above said countries is at least 5 years. Residential requirement for citizenship through naturalization for others is 11 years.

- The Act applies to all States and Union Territories of the country.

- The beneficiaries of Citizenship Amendment Act can reside in any state of the country.

- In 1964, the govt. brought in the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order.

- Advocates not below the age of 35 years of age with at least 7 years of practice (or) Retired Judicial Officers from the Assam Judicial Service (or) Retired IAS of ACS Officers (not below the rank of Secretary/Addl. Secretary) having experience in quasi-judicial works.

- The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has amended the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964, and has empowered district magistrates in all States and Union Territories to set up tribunals (quasi-judicial bodies) to decide whether a person staying illegally in India is a Foreigner or Not.

- Earlier, the powers to constitute tribunals were vested only with the Centre.

- Typically, the tribunals there have seen two kinds of cases: those concerning persons against whom a reference has been made by the border police and those whose names in the electoral roll has a “D”, or “doubtful”, marked against them.

Who are Illegal Immigrants?

- According to the Citizenship Act, 1955, an illegal immigrant is one who enters India without a valid passport or with forged documents, or a person who stays beyond the visa permit.

What is NRC?

- The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is meant to identify a bona fide citizen.

- In other words, by the order of the Supreme Court of India, NRC is being currently updated in Assam to detect Bangladeshi nationals who might have entered the State illegally after the midnight of March 24, 1971.

- The date was decided in the 1985 Assam Accord, which was signed between the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the AASU.

- The NRC was first published after the 1951 Census in the independent India when parts of Assam went to the East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

- The first draft of the updated list was concluded by December 31, 2017.

Arguments against the Act:

- The fundamental criticism of the Act has been that it specifically targets Muslims. Critics argue that it is violative of Article 14 of the Constitution (which guarantees the right to equality) and the principle of secularism.

- India has several other refugees that include Tamils from Sri Lanka and Hindu Rohingya from Myanmar.

- They are not covered under the Act.

- Despite exemption granted to some regions in the North-eastern states, the prospect of citizenship for massive numbers of illegal Bangladeshi migrants has triggered deep anxieties in the states.

- It will be difficult for the government to differentiate between illegal migrants and those persecuted.

Arguments in Favour:

- The government has clarified that Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh are Islamic republic’s where Muslims are in majority hence they cannot be treated as persecuted minorities. It has assured that the government will examine the application from any other community on a case to case basis.

- This Act is a big boon to all those people who have been the victims of Partition and the subsequent conversion of the three countries into theocratic Islamic republics.

- Citing partition between India and Pakistan on religious lines in 1947, the government has argued that millions of citizens of undivided India belonging to various faiths were staying in Pakistan and Bangladesh from 1947.

- The constitutions of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh provide for a specific state religion. As a result, many persons belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian communities have faced persecution on grounds of religion in those countries.

- Many such persons have fled to India to seek shelter and continued to stay in India even if their travel documents have expired or they have incomplete or no documents.

- After Independence, not once but twice, India conceded that the minorities in its neighbourhood is its responsibility. First, immediately after Partition and again during the Indira-Mujib Pact in 1972 when India had agreed to absorb over 1.2 million refugees. It is a historical fact that on both occasions, it was only the Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and Christians who had come over to Indian side.

Centre yet to notify rules of Citizenship Amendment Act

10, Jan 2022

Why in News?

- The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) did not notify the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 rules even the third extended deadline after the Act was passed.

About the News:

- The CAA was passed by the Lok Sabha in Dec 9, 2019, by the Rajya Sabha on Dec 11, 2019 and was assented by the President on December 12, 2019.

- The MHA issued a notification later that the provisions of the act will come into force from Jan 10, 2020.

- January 9 was the last day of an extension it sought from the two parliamentary committees in the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha to frame the rules.

- But still the rules are not yet notified.

- The legislation cannot be implemented without the rules being notified.

About the CAA and Foreigners Tribunal:

- The Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019 that seeks to give citizenship to refugees from the Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, Sikh and Zoroastrian communities fleeing religious persecution from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, who came to India before 31st December, 2014.

- Residential Requirement for citizenship through naturalization from the above said countries is at least 5 years. Residential requirement for citizenship through naturalization for others is 11 years.

- The Act applies to all States and Union Territories of the country.

- The beneficiaries of Citizenship Amendment Act can reside in any state of the country.

- In 1964, the govt. brought in the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order.

- Advocates not below the age of 35 years of age with at least 7 years of practice (or) Retired Judicial Officers from the Assam Judicial Service (or) Retired IAS of ACS Officers (not below the rank of Secretary/Addl. Secretary) having experience in quasi-Judicial Works.

- The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has amended the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964, and has empowered district magistrates in all States and Union Territories to set up tribunals (quasi-judicial bodies) to decide whether a person staying illegally in India is a foreigner or not.

- Earlier, the powers to constitute tribunals were vested only with the Centre.

- Typically, the tribunals there have seen two kinds of cases: those concerning persons against whom a reference has been made by the border police and those whose names in the electoral roll has a “D”, or “doubtful”, marked against them.

Who are Illegal Immigrants?

- According to the Citizenship Act, 1955, an illegal immigrant is one who enters India without a valid passport or with forged documents, or a person who stays beyond the Visa Permit.

What is NRC?

- The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is meant to identify a bona fide citizen.

- In other words, by the order of the Supreme Court of India, NRC is being currently updated in Assam to detect Bangladeshi nationals who might have entered the State illegally after the midnight of March 24, 1971.

- The date was decided in the 1985 Assam Accord, which was signed between the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the AASU.

- The NRC was first published after the 1951 Census in the independent India when parts of Assam went to the East Pakistan, now Bangladesh.

- The first draft of the updated list was concluded by December 31, 2017.

Arguments against the Act:

- The Fundamental Criticism of the Act has been that it specifically targets Muslims. Critics argue that it is violative of Article 14 of the Constitution (which guarantees the right to equality) and the principle of secularism.

- India has several other refugees that include Tamils from Sri Lanka and Hindu Rohingya from Myanmar. They are not covered under the Act.

- Despite exemption granted to some regions in the North-eastern states, the prospect of citizenship for massive numbers of illegal Bangladeshi migrants has triggered deep anxieties in the states.

- It will be difficult for the government to differentiate between Illegal Migrants and those Persecuted.

Arguments in Favour:

- The government has clarified that Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh are Islamic republic’s where Muslims are in majority hence they cannot be treated as persecuted minorities. It has assured that the government will examine the application from any other community on a case to case basis.

- This Act is a big boon to all those people who have been the victims of Partition and the subsequent conversion of the three countries into theocratic Islamic republics.

- Citing partition between India and Pakistan on religious lines in 1947, the government has argued that millions of citizens of undivided India belonging to various faiths were staying in Pakistan and Bangladesh from 1947.

- The constitutions of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh provide for a specific state religion. As a result, many persons belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian communities have faced persecution on grounds of religion in those countries.

- Many such persons have fled to India to seek shelter and continued to stay in India even if their travel documents have expired or they have incomplete or no documents.

- After Independence, not once but twice, India conceded that the minorities in its neighbourhood is its responsibility. First, immediately after Partition and again during the Indira-Mujib Pact in 1972 when India had agreed to absorb over 1.2 million refugees. It is a historical fact that on both occasions, it was only the Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and Christians who had come over to Indian side.

CENSUS – CHALLENGES & IMPORTANCE

14, Feb 2020

Context:

- Instances of the field enumerators coming under attack for some of the ongoing NSS surveys due to the mistrust over CAA and NRC, is an issue for concern. The House Numbering and Houselisting operation and the updation of the National Population Register, set to begin in April for Census 2021, is also expected to be welcomed with such hostility among the citizenry.

What is Census?

- Population Census is the total process of collecting, compiling, Analyzing or otherwise disseminating demographic, economic and social data pertaining, at a specific time, of all persons in a country or a well-defined part of a country.

- As such, the census provides a snapshot of the country’s population and housing at a given point of time.

Why Census?

- The census provides information on size, distribution and socio-economic, demographic and other characteristics of the country’s population.

- The data collected through the census are used for administration, planning and policy making as well as management and evaluation of various programmes by the government, NGOs, researchers, commercial and private enterprises, etc.

- Census data is also used for demarcation of constituencies and allocation of representation to parliament, State legislative Assemblies and the local bodies.

- Researchers and demographers use census data to Analyze growth and trends of population and make projections.

- The census data is also important for business houses and industries for strengthening and planning their business for penetration into areas, which had hitherto remained uncovered.

History of Census in India

- The earliest literature ‘Rig-Veda’ reveals that some kind of population count was maintained during 800-600 BC in India.

- The ‘Arthashastra’ by ‘Kautilya’ written in the 3rd Century BC prescribed the collection of population statistics as a measure of state policy for taxation.

- It contained a detailed description of methods of conducting population, economic and agricultural censuses.

- During the regime of the Mughal king Akbar, the administrative report ‘Ain-e-Akbari’ included comprehensive data pertaining to population, industry, wealth and many other characteristics.

- A systematic and modern population census, in its present form was conducted non synchronously between 1865 and 1872 in different parts of the country.

- This effort culminating in 1872 has been popularly labeled as the first population census of India.

- However, the first synchronous census in India was held in 1881. Since then, censuses have been undertaken once every ten year.

Stages of Census

a) Preparatory Work

b) Enumeration

c) Data processing

d) Evaluation of results

e) Analysis of results

f) Dissemination of the results

g) Systematic recording of Census experience

- The preparatory work of census includes the House Numbering and Houselisting operation.

Census 2021:

- The 2021 Census of India, also the 16th Indian Census, will be taken in 2021.

- The Registrar General and Census Commissioner through an official notification has announced that 31 questions will be collected by the enumerators from every household during the house listing and housing census exercise.

- The other questions related to the main source of lighting, whether the family has access to a toilet, waste water outlet, availability of kitchen and LPG or PNG connection and main fuel used for cooking were also to be asked by the enumerators.

- It is a massive exercise and will be massively expensive, involving about 30 lakh enumerators and field functionaries (generally government teachers and those appointed by state governments).

- First Digital Census: The data collected during the 2021 Census will be stored electronically.

- Earlier, the census data used to be preserved for 10 years and then it was destroyed. From the 2021 Census it will be stored forever in electronic format.

Issues with the Census 2021:

- The NPR first prepared in 2010 under the provisions of the Citizenship Act, 1955 and Citizenship Rules, 2003 and subsequently updated in 2015 — will also be updated along with house listing and housing Census (except in Assam).

- Amid the backdrop of views of citizenry against CAA and NPR, the National Sample Survey Office field officials have been attacked in some areas of Kerala, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal mistaken as Census officials.

- At its core, the fears of a tainted Census stem from the NPR, breaking one of the cardinal rules in objective data collection, the preservation of anonymity.

- As he NPR is more likely to result in questioning their citizenship, people may choose to obfuscate or misreport.

- Because the NPR and Census are to be run concurrently — and both are under the auspices of the Registrar General of the ministry of home affairs (also the key architect and driver of the CAA) — this loss of credible information is likely to extend to the Census.

- Given that those born after July 1987 will have to offer proof of their parents’ citizenship, and some segments of citizens, especially Muslims, are particularly vulnerable to having their citizenship questioned, there will be considerable incentives for people to misreport age, religion and language data.

- The Census data is, by definition, a means to serve government goals. The compact between a State and its citizens is built on a foundation of trust, one that is based on a minimal presumption that people are citizens of that State to begin with. The erosion of that trust will undermine the Indian State’s ability to gather credible data and ultimately makes the government incapable of framing effective policies for its people.

ASSAM NRC: WHO IS AN INDIAN CITIZEN? HOW IS IT DEFINED?

31, Aug 2019

Why in News?

- In the run-up to the publication of the final National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam, citizenship has become the most talked about topic in the country.

- The Assam government has been taking various steps in relation to those who will be left out of the NRC, while the Supreme Court last week rejected a plea to include those born in India between after March 24, 1971 and before July 1, 1987 unless they had ancestral links to India.

- In any other Indian state, they would have been citizens by birth, but the law is different for Assam.

How is Citizenship Determined in India?

- Citizenship signifies the relationship between individual and state. It begins and ends with state and law, and is thus about the state, not people. Citizenship is an idea of exclusion as it excludes non-citizens.

- There are two well-known principles for grant of citizenship:

- Jus soli: confers citizenship on the basis of place of birth,

- Jus sanguinis: gives recognition to blood ties.

- From the time of the Motilal Nehru Committee (1928), the Indian leadership was in favour of the enlightened concept of jus soli.

- The racial idea of jus sanguis was rejected by the Constituent Assembly as it was against the Indian ethos.

- Citizenship is in the Union List under the Constitution and thus under the exclusive jurisdiction of Parliament. The Constitution does not define the term ‘citizen’ but gives, in Articles 5 to 11, details of various categories of persons who are entitled to citizenship.

- Unlike other provisions of the Constitution, which came into being on January 26, 1950, these articles were enforced on November 26, 1949 itself, when the Constitution was adopted.

- However, Article 11 itself confers wide powers on Parliament by laying down that “nothing in the foregoing provisions shall derogate from the power of Parliament to make any provision with respect to the acquisition and termination of citizenship and all matters relating to citizenship”. Thus, Parliament can go against the citizenship provisions of the Constitution.

- The Citizenship Act, 1955 was passed and has been amended four times — in 1986, 2003, 2005, and 2015. The Act empowers the government to determine the citizenship of persons in whose case it is in doubt. However, over the decades, Parliament has narrowed down the wider and universal principles of citizenship based on the fact of birth. Moreover, the Foreigners Act places a heavy burden on the individual to prove that he is not a foreigner.

So, who is, or is not, a citizen of India?

- Article 5: It provided for citizenship on commencement of the Constitution. All those domiciled and born in India were given citizenship. Even those who were domiciled but not born in India, but either of whose parents was born in India, were considered citizens. Anyone who had been an ordinary resident for more than five years, too, was entitled to apply for citizenship.

- Article 6: Since Independence was preceded by Partition and migration, Article 6 laid down that anyone who migrated to India before July 19, 1949, would automatically become an Indian citizen if either of his parents or grandparents was born in India. But those who entered India after this date needed to register themselves.

- Article 7: Even those who had migrated to Pakistan after March 1, 1947 but subsequently returned on resettlement permits were included within the citizenship net. The law was more sympathetic to those who migrated from Pakistan and called them refugees than to those who, in a state of confusion, were stranded in Pakistan or went there but decided to return soon.

- Article 8: Any Person of Indian Origin residing outside India who, or either of whose parents or grandparents, was born in India could register himself or herself as ab Indian citizen with Indian Diplomatic Mission.

- 1986 amendment: Unlike the constitutional provision and the original Citizenship Act that gave citizenship on the principle of jus soli to everyone born in India, the 1986 amendment to Section 3 was less inclusive as it added the condition that those who were born in India on or after January 26, 1950 but before July 1, 1987, shall be Indian citizen.

- Those born after July 1, 1987 and before December 4, 2003, in addition to one’s own birth in India, can get citizenship only if either of his parents was an Indian citizen at the time of birth.

- 2003 amendment: The then NDA government made the above condition more stringent, keeping in view infiltration from Bangladesh. Now the law requires that for those born on or after December 4, 2004, in addition to the fact of their own birth, both parents should be Indian citizens or one parent must be Indian citizen and other should not be an illegal migrant. With these restrictive amendments, India has almost moved towards the narrow principle of jus sanguinis or blood relationship. This lays down that an illegal migrant cannot claim citizenship by naturalisation or registration even if he has been a resident of India for seven years.

- Citizenship (Amendment) Bill: The amendment proposes to permit members of six communities — Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan — to continue to live in India if they entered India before December 14, 2014. It also reduces the requirement for citizenship from 11 years out of the preceding 14 years, to just 6 years.

- Two notifications also exempted these migrants from the Passport Act and Foreigner Act. A large number of organisations in Assam protested against this Bill as it may grant citizenship to Bangladeshi Hindu illegal migrants.

What is different in Assam?

- The Assam Movement against illegal immigration eventually led to the historic Assam Accord of 1985, signed by Movement leaders and the Rajiv Gandhi government. Accordingly, the 1986 amendment to the Citizenship Act created a special category of citizens in relation to Assam.

- The newly inserted Section 6A laid down that all persons of Indian origin who entered Assam before January 1, 1966 and have been ordinary residents will be deemed Indian citizens.

- Those who came after 1 January, 1966 but before March 25, 1971, and have been ordinary residents, will get citizenship at the expiry of 10 years from their detection as foreigner. During this interim period, they will not have the right to vote but can get an Indian passport.

- Identification of foreigners was to be done under the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act, (IMDT Act), 1983, which was applicable only in Assam while the Foreigners Act, 1946 was applicable in the rest of the country.

- The provisions of the IMDT Act made it difficult to deport illegal immigrants. On the petition of Sarbananda Sonowal (now Chief Minister), the Act was held unconstitutional and struck down by the Supreme Court in 2005.

- This was eventually replaced with the Foreigners (Tribunals of Assam) Order, 2006, which again was struck down in 2007 in Sonowal II.

- In the IMDT case, the court considered classification based on geographical considerations to be a violation of the right to equality under Article 14. In fact, another such variation was already in place. While the cut-off date for Western Pakistan is July 19, 1949, for Eastern Pakistan the Nehru-Liaquat Pact had pushed it to 1950.

New Rules on Granting Citizenship

30, Oct 2018

The government has authorised 16 collectors across seven states to register members of minority communities from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh as Indian citizens.

About:

- The collectors of Raipur (Chhattisgarh), Ahmedabad, Gandhinagar and Kutch (Gujarat), Bhopal and Indore (Madhya Pradesh), Nagpur, Mumbai, Pune and Thane (Maharashtra), Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Jaipur (Rajasthan), Lucknow (Uttar Pradesh) and West Delhi and South Delhi were empowered to extend citizenship rights to eligible people under the Citizenship Act-1955. The notification said that the home secretary of the state or union territory concerned has also been given the same power in case the applicant is not a resident of the mentioned districts, subjects to certain conditions.

- Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from the three countries can avail of this facility. Under the new rules, notified on October 24, the migrants can apply online, and the verification reports or the security clearance reports of the applicants shall be made available to the Centre through an online portal.

The conditions are:

- The application for registration as a citizen of India or grant of certificate of naturalisation as citizen of India under the said rules should be made by the applicant online,

- The verification of the application would be done simultaneously by the collector or the secretary at the district or state levels, and the application and the reports thereon will be made accessible simultaneously to the central government through an online portal.

- In addition, the collector or secretary is allowed to conduct probes for ascertaining the applicant’s suitability. The instructions issued by the central government from time to time will also have to be strictly adhered to by the authorities concerned. Furnish a copy thereof to the Central government within seven days of registration.

Impact:

- The illegal immigrants who are to be granted the benefit of this legislation are to qualify for citizenship only on the basis of religion; a requirement that goes against one of the basic tenets of the Indian Constitution, secularism.

- The relaxation criteria for eligibility of illegal migrants to gain citizenship is unreasonable. With no explanation given as to the inclusion of this clause, it is prima facie unconstitutional, failing the test of reasonability contained in Article 14 (Right to Equality) of the Constitution and corrupting the “basic structure doctrine” (Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala1973).

- The most glaring discrepancy is that it categorically states that religious minorities from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh will no longer be treated as illegal immigrants. It specifically names six religions, that is, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians. Muslims and Jews have been deliberately kept out of the ambit. Even though some of these religions are also religious minorities in India, it is notable that four of these six religions fall under the ambit of Hindu personal law.

- As of today, the largest religious minority in India is that of Muslims it makes little sense to deliberately keep them out of the ambit of this bill.

Background:

- A parliamentary committee has been examining the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2016, which proposes to grant citizenship to six persecuted minorities: Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians and Buddhists who came to India from Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh before 2014.

- As the Bill is pending, the Home Ministry gave powers to the Collectors in Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi to grant citizenship and naturalisation certificates to the migrants under Sections 5 and 6 of the Citizenship Act, 1955. No such power has been delegated to Assam officials.

- Official data put the number of such migrants in India at two lakhs. There are 400 Pakistani Hindu refugee settlements in Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Bikaner and Jaipur. Hindu migrants from Bangladesh mostly live in West Bengal and north-eastern States.

Citizenship:

- The constitution of India gives ‘Single Citizenship” for all its citizens India. This implies that there is no disparate domicile for a state. Provisions for citizenship are mentioned in Article 5 to 11 in Part II of the Constitution. Individuals who are not Indian Citizens are considered Aliens.

- The Citizenship Act, 1955 also deals with the citizenship. However, neither of these legislations have defined citizenship clearly and only provide the prerequisites for a “natural” person to acquire Indian citizenship.

Indian Citizenship can be acquired by following four means:

- Citizenship by birth

- Citizenship by descent

- Citizenship by registration

- Citizenship by naturalization

Termination/Renunciation of citizenship:

Renunciation:

Renunciation is covered under Section 8 of the Citizenship Act 1955. If an adult makes a declaration of renunciation of Indian Citizenship, he would lose Indian Citizenship. Along with him, any minor child of that person also loses Indian Citizenship from the date of renunciation. The child has the right to resume Indian Citizenship when he turns eighteen.

Termination:

It is covered under Section 9 of Citizenship Act 1955. Any Indian Citizen who by naturalization or registration acquires the citizenship of another country shall cease to be a Citizen of India.

National Population Register

17, Jul 2018

- The National Population Register (NPR) is a Register of usual residents of the country. It is being prepared at the local Village level, sub District Tehsil/Taluk level, District, State and National level under provisions of the Citizenship Act 1955 and the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003.

- Which was updated in all India level by 2015-16 except in Assam and Meghalaya.

- The National Population Register (NPR) is a database of the identities of all Indian residents. The database is maintained by the Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- The NPR project, inspired by a citizenship card project conceived by BJP patriarch LK Advani, was launched during former home minister P Chidambaram’s tenure in 2009-2010.

Goal:

- The objective of the NPR is to create a comprehensive identity database in the country with full identification and other details by registering each and every usual resident in the country.

- This would help in better targeting the benefits and services under the Government schemes/programmes, improve planning and prevent identity fraud.

- The goal for NPR is almost the same as for UDAID, which issues Aadhar cards. It is to improve implementation of the economic policies of the government and its various programs, in so far as they affect different segments of the population.

- NPR and UIDAI work closely together to create a database of Indian residents.

- In view of the growing need for a credible identification system in the country due to various factors, like internal security, illegal migration etc, India is contemplating the preparation of a National Population Register (NPR) by collecting specific information on each person residing in the country.

- The proposed NPR would contain such information as, name, sex, date of birth, current marital status, name of father, mother and spouse, educational level attained, nationality, occupation/activity pursued, present and permanent addresses.

- The database would also contain the photograph and finger biometry of persons above the age of 15 years. Under this scheme, every individual would be assigned a unique National Identification Number (NIN).

- As per Section 14A of the Citizenship Act as amended in 2004, it is compulsory for every citizen of the country to register in the National Register of Indian Citizens (NRIC).

- The creation of the National Population Register (NPR) is the first step towards preparation of the NRIC. Out of the universal dataset of residents, the subset of citizens would be derived after due verification of the citizenship status.

- Therefore, it is compulsory for all usual residents to register under the NPR.

- An NRI is not a usual resident of the country. Therefore, they would not be in the NPR till they are non-residents. When they come back to India and take up usual residence within the country, they will be included in the NPR.

- Providing any false information would attract penalties under Citizenship Rules 2003.

Under the NPR Project, the following activities are undertaken:

- House listing by enumerator.

- Scanning of NPR schedules.

- Storing data in a digital format.

- Biometric enrolment and consolidation.

- Correction and validation of information collected.

- Deduplication by UIDAI and issuance of Aadhaar number.

- Consolidation of data at the Census Commissioner’s office.

- There is also a proposal to issue Resident Identity Cards to all usual residents in the NPR of 18 years of age and above is under consideration of the Government. This proposed Identity Card would be a smart card and would bear the Aadhaar number.

Agencies Involved:

Several government agencies are working towards the creation of this NPR. These includes:

1. Registrar General Of India

2. The Department of Electronics and Information

3. Department of Electronics and Accreditation of Computer Classes

4. CSC e-Governance Services India Ltd and Managed Service Providers (MSPs).

Process:

- During the first phase of Census 2011, enumerators have visited every household and have collected the details required for the NPR in a prescribed format.

- These forms have been scanned and the data has been entered into an electronic database in two languages – the State language and in English.

- Biometric attributes – photograph, ten fingerprints and two iris images are being added to the NPR database by organizing enrolment camps in each local area.

- The enrolment will be done in the presence of Government servants appointed for this purpose. All usual residents who are above 5 years of age should attend the even if their biometrics have been captured under Aadhaar.

- For persons not enrolled under Aadhaar, UIDAI can also register themselves in the enrolment camps.

- No specific documents are required for registration in the NPR.

- If the household has not been covered during the census 2011 or if the individual has changed residence after the Census, a new will be given at the camp and have to be filled up there.

- The filled-in forms will be submitted to the Government official, present at the camp. These forms will be verified by the authorities and the individuals biometric details will be captured during the next round of biometric camps.

Connection between NPR and Aadhaar:

The data collected in NPR will be sent to UIDAI for de-duplication and issue of Aadhaar Number. Thus the register will contain three elements of data:

- Demographic data

- Biometric data and

- The Aadhaar (UID Number)

- A person who has already enrolled with still has to register under NPR.

NPRIC:

- The Indian government is also creating a National Register of Indian Citizens, a subset of the National Population Register.

- The National Register of Indian Citizens (NRIC) will be a Register of citizens of the country.

- It will be prepared at the local (Village level), sub District (Tehsil/Taluk level), District, State and National level after verifying the details in the NPR and establishing the citizenship of each individual.

- It is compulsory for every citizen of the country to register in the NRIC.

- In simple terms, the NRIC is a register of Indian citizens. It will hold online the details of every Indian citizen.

- The NRIC will be prepared after the verification of the information in the NPR and establishing the citizenship of each individual.

Drawback:

- NPR was a slow process because it enrolled people in accordance with households, not just individuals.

- A register based census is impossible in India given its size and complexities.

- Creating the database is a costly and cumbersome exercise.

- Update the database dynamically, capturing every event of birth, death and migration on a real time basis across the length and breadth of the country and keep it live at all points of time is a difficult exercise.

- Whether the Register would replace the Census in due course is an unanswerable question.

- Register based information, is by its nature, not confidential and hence may be prone to other influences. • The Register General and Census Commissioner of India has turned down state governments’ request on sharing data from the National Population Register (NPR). Due to reason of privacy concerns.

Benefit:

- There are several databases in India like electors list, driving licenses, passports, PAN cards (Income Tax), list of persons below the poverty line, ration cards, farmers cards to name a few. All these have a limited reach and are standalone databases.But NPR is a comprehensive one.

- In order to avoid duplication, save costs and allow interoperability, a standard database covering the entire population is an urgent necessity. The fundamental purpose of the NPR is to provide a credible database for identification

- Cross tabulation of various indicators give policy planners and others robust inputs for programme planning and implementation on a full count basis.

- The Register coupled with sample surveys would allow the generation of many of the indicators

- It would definitely , shorten and simplify the existing Census and thereby enhance its qualitative aspects. This would also enable the conduct of Census at more frequent intervals instead of once in a decade.

NPRIC in Assam:

- Assam is the only state to have its own register of citizens.

- Assam historically has seen an influx of immigrants. Before independence, the Britishers brought in plantation workers from present-day Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

- In 1904, Bengal was divided into East Bengal, West Bengal and Assam.

- Post the 1971 war, a large number of people migrated from East Pakistan to Assam and West Bengal.

- The government then made several efforts to send back the illegal immigrants but failed. This large-scale immigration affected the ethnic balance of the original population.

- The first NRC was created in 1951 following the Census of the same year. It was basically a serialised list of houses and property holdings in every Indian village with the number of people residing in them along with their names.

- However, by the 1980s, there had been demands in Assam to update the list because the indigenous Assamese feel that the immigrants have outnumbered them and are eating into their limited resources and rights.

- on the heels of the anti-illegal foreigners’ movement in Assam in 1980, the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) and Assam Gana Parishad in 1980 submitted a memorandum to the Centre, seeking the ‘updation’ of the list.

- The move was aimed at protecting the indigenous culture of Assam from illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

- Finally, in 1985, the Assam Accord was signed after which the agitation culminated.

- Following the Accord, an amendment to the Citizenship Act of 1955 under section 6(A) gave Indian citizenship to all migrants who came to Assam before the midnight of March 24, 1971.

- The updated NRC will count only those as Assam citizens who can prove their residency on or before March 21, 1971. This means that all those not included in the list run the risk of being rendered, illegal immigrants.

- Thus National Register of Citizens is designed to identify who is a citizen and who is an immigrant in Assam.

- While building such a list (a register of citizens, in this case) is geared towards ensuring that it becomes easier to deal problems of governing citizens and immigrants.

- The present updating process began in 2015, following a Supreme Court directive to the government to keep up with the Assam Accord of 1985.

The date March 24, 1971, was decided because the Bangladesh Liberation war started on March 25, 1971.

Issues:

- All those whose names are not there in the draft NRC will get another chance at explaining/complaining to the NRC authorities. But those who do not have their names in the final NRC will be deemed as not a citizen of the country. They will have to fight the battle in the foreigners tribunals to prove themselves as Indians.

- This massive exercise threatens to strip even genuine Indians of their citizenship if they are unable to produce documents that prove their ancestors resided in Assam before 1971.

- Is being justified with the aim to identify and segregate illegal Bangladeshi migrants.

- United Nations special rapporteurs said that the NRC updation exercise may be biased against the Bengali Muslim minority.

Politically, however, it offers a polarised religious and regional plank on which elections are fought, won and lost.